All throughout my university years there has always been one word that has been mentioned whenever possible: biodiversity.

Biodiversity is one of those words that have become part of our daily language together with sustainability and greenwashing. It’s difficult to go a day without hearing these important words.

This raises the question though, do we even know what biodiversity means? And if so, what is really the point with it, why should we care?

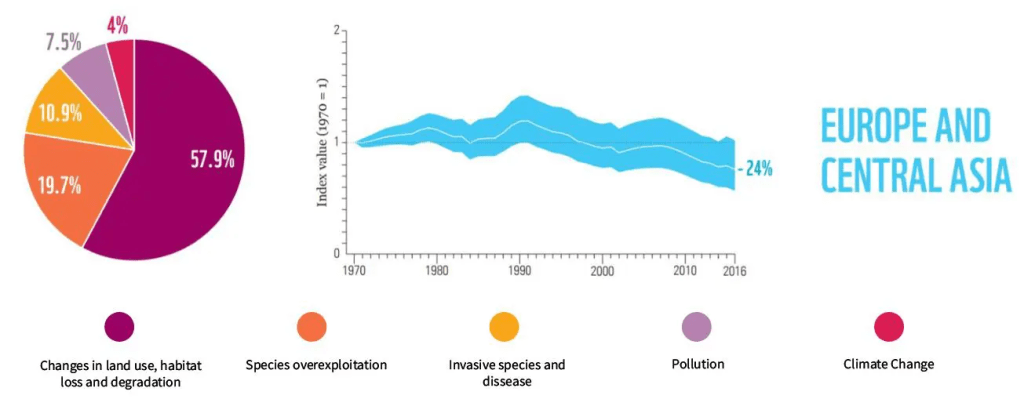

According to the Smithsonian, biodiversity is the variety of all living things and their interactions1. And sadly this essential variety is on its way down.

Biodiversity is on its way down.2

Why is it going down?

The age we live in now is called “The Anthropocene”, which is used to describe the most recent period in Earth’s history when human activity started to have a significant impact on the planet’s climate and ecosystems3.

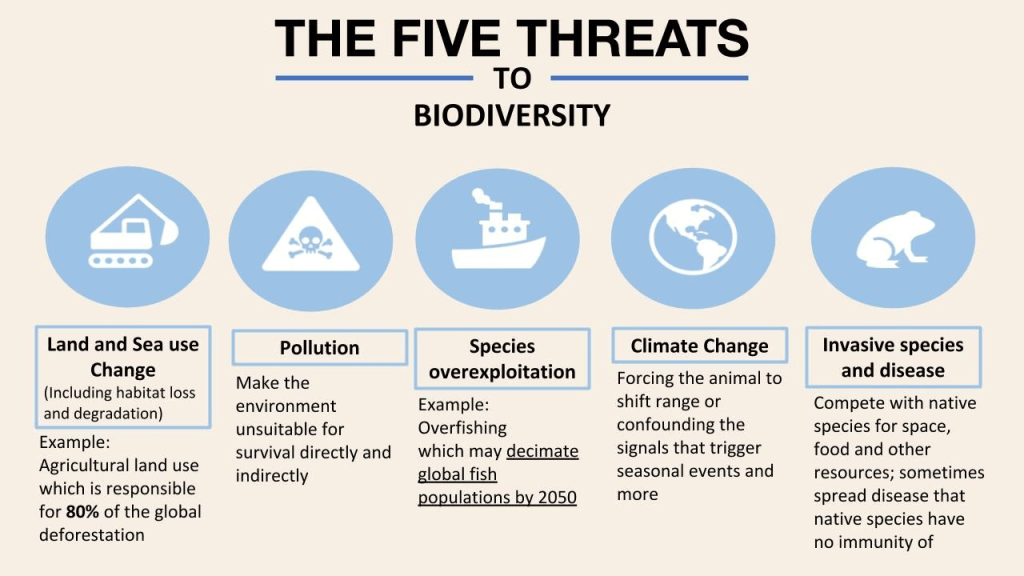

We are impacting nature in a way that has never been seen before. WWF’s Living Planet Report from 2020 lists the 5 biggest threats to biodiversity:

The five threats to biodiversity4

The loss of biodiversity is a complicated issue, with its fair share of reasons.

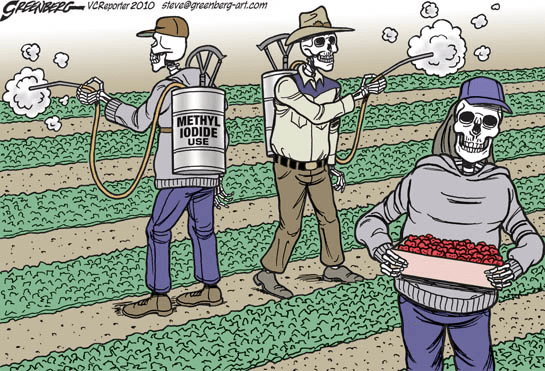

One of the biggest threats is how we use our land; deforestation, pesticides, monocultures and toxic runoffs, we have gradually but surely made it impossible for many different species to exist.

Why should we care?

We like to think that we are different and somehow segregated from the outside world. But this can’t be further from the truth. Whatever happens outside our homes will have a big impact on us.

A healthy planet means a resilient planet, and biodiversity is the cornerstone of that health and resilience. The variety of species and ecosystems performs numerous essential functions that support life on Earth, including human life.

Look at it this way; imagine you work in a team where everybody has the same education, the same experience and the same talents. Now imagine that you are in another team, made up of different people with different backgrounds and talents. Which team will most likely better manage new problems?

This is an extremely simplified way of looking at biodiversity, but hopefully my point comes across.

What can we do?

It’s sometimes difficult to just sit and watch as the world falls apart, and not being able to do anything about it.

Sadly, the biggest results will not be achieved by individuals, but we can still make a mark if we work together.

Maybe the best thing you can do (if you are so lucky to have a garden), consider not cutting your lawn. Taller grass helps local insects survive and thrive, but be sure that there are no invasive species. It can also be a good idea to buy local plants which can have a new home with you.

What are your thoughts on biodiversity? Why do you think we should care and what can we do as individuals?

Sources:

- https://naturalhistory.si.edu/education/teaching-resources/life-science/what-biodiversity ↩︎

- https://earth.org/data_visualization/biodiversity-loss-in-numbers-the-2020-wwf-report/ ↩︎

- https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/anthropocene/ ↩︎

- https://earth.org/data_visualization/biodiversity-loss-in-numbers-the-2020-wwf-report/ ↩︎